A new year arrives, we have a new project to be getting on with and I should be concentrating on that but I just can’t stop my head from turning backwards. To be more precise I can’t stop musing on those moments when music and politics collide and the effect they’ve had on my life. This was all sparked off by one of my Christmas presents: “The Future is Unwritten”, a documentary about the life of Joe Strummer. I found it pretty affecting. There was the recognition of similar experiences (to some extent) but more than that was a realisation of just what an inheritance the sensibilities of that history have been. I was powerfully struck by how the refrains re-ignited by watching that film had structured the territory upon which I’d lived out my life. Even Strummer’s vision of heaven as a series of campfires, that we are drawn towards and drift between, struck a real cord. Taking me right back to formative trips to 1980’s Free festivals.One of the things it sparked of in me was the re-occurrence of a sense of shared alternative history, formed out of collective experiences; political, musical or both. It’s a sort of minor history, in that it’s deviation from the standard history but I was reminded just how virulent and widespread it is. It might be a history that’s only sporadically actualised but it’s no less real than one David Starkey might write about. That sense of a history was amplified by stumbling across blogs like History is made at night and Greengalloway and recognising in them a common narrative with shared interests, style and attitude rooted in common collective bodily experiences. I’m always interested in the effects such experiences have on a life, what they leaves behind and then what can be done with those effects that are left lying around inside different bodies. Interestingly one of the blogs, Greengalloway had previously got excited about some of our writing, even going so far as to say we’d kept him up all night. It was great, but not altogether surprising that he instantly recognised what we were talking about with moments of excess but it was even better that we had managed to re-ignite one of those affective refrains lodged in his body.

A new year arrives, we have a new project to be getting on with and I should be concentrating on that but I just can’t stop my head from turning backwards. To be more precise I can’t stop musing on those moments when music and politics collide and the effect they’ve had on my life. This was all sparked off by one of my Christmas presents: “The Future is Unwritten”, a documentary about the life of Joe Strummer. I found it pretty affecting. There was the recognition of similar experiences (to some extent) but more than that was a realisation of just what an inheritance the sensibilities of that history have been. I was powerfully struck by how the refrains re-ignited by watching that film had structured the territory upon which I’d lived out my life. Even Strummer’s vision of heaven as a series of campfires, that we are drawn towards and drift between, struck a real cord. Taking me right back to formative trips to 1980’s Free festivals.One of the things it sparked of in me was the re-occurrence of a sense of shared alternative history, formed out of collective experiences; political, musical or both. It’s a sort of minor history, in that it’s deviation from the standard history but I was reminded just how virulent and widespread it is. It might be a history that’s only sporadically actualised but it’s no less real than one David Starkey might write about. That sense of a history was amplified by stumbling across blogs like History is made at night and Greengalloway and recognising in them a common narrative with shared interests, style and attitude rooted in common collective bodily experiences. I’m always interested in the effects such experiences have on a life, what they leaves behind and then what can be done with those effects that are left lying around inside different bodies. Interestingly one of the blogs, Greengalloway had previously got excited about some of our writing, even going so far as to say we’d kept him up all night. It was great, but not altogether surprising that he instantly recognised what we were talking about with moments of excess but it was even better that we had managed to re-ignite one of those affective refrains lodged in his body.

I really like the image of affective refrains created in more intensive moments behaving like disorganising, destabilising barbs of other potential presents, pasts and futures lodged in our organised bodies and occasionally helping to dissolve them. And I want to say bodies not just subjectivities because as we know these refrains can be corporeal – how we hold our bodies, where our bodies end –Cue Hives anecdote 3a. One of the pitfalls with all this is it’s a little like looking at a photo album – a narrative constructed out of flashes means nostalgia must be guarded against. But then again we can’t just leave the past alone as though it’s all over. The past is unwritten or at the very least every present includes a re-writing of the past. Relatedly time is not homogenous, there are periods of intensification and drastic divergence when the future does seem unwritten and then there are periods of cloying, clagging impotence when the present seems utterly effaced by an unalterable but still fictional future.

Anyway something else I watched last week was Paul Morley’s “Pop! What is it good for?” and one of the things I got from that was the idea that songs carry ‘invisibles’ around with them. The power of pop is that we can’t get it out of our heads. It enters by osmosis and provides us with the refrains out of which we build our worlds. There was a section where Richard X was commenting on his mash-up “Freak Like Me”. He claimed that the creativity of the mash-up is recognising and playing with the invisibles – the affects, feelings and associations that songs bring up. It’s the mashing up of these that are the element of creativity. More than just Mash-ups all pop trades on these invisibles As it eats itself. In another section Suggs talked about how the influence of vaudeville had unconsciously snuck into Madness, and punk, through the influence of parents and wider culture. This is another way of thinking about invisibles. In fact that same point was brilliantly made in Julian Temple’s other Punk film: “The Filth and the Fury” when he shows Max Wall’s influence on the Johnny Rotten persona.

Pop trades on possibilities, re-invention. On the creation of the new out of repetition and imitation. At its best it’s about the introduction of a strangeness into the everyday. That strangeness is a moment in the repotentialisation of everyday life but capital is about depotentialisation. Capital needs to subordinate all life and creativity to it’s own life, that is it’s need to grow. And surely that is the story of pop music – How the residue of moments of autonomous creativity are carried as invisibles into music made for purely commercial reasons. Then vice versa how the potential of those moments and affects are eaten by capital’s need for a novelty that changes nothing. Yet the whole idea of recuperation always seems too pat and easily done. What about the idea that capital constantly has to eat stuff that contain elements it finds indigestible. As capital circulates, as it has to, it also spreads those invisible indigestibles. As a quote from Howard Slater puts it:

What should be stated is that music is not revolutionary per se but carries with it many presuppositions of an awareness of a need for social change; not least in terms of its activation of desire in the listener, its opening up of unconscious and imaginary terrains and its proclivity towards social interaction. It can be rhetorical, propagandist and a source of optimism and hope, and from jazz scenes through anarcho-punk to rave and techno, music has always been attached to counter-cultural and political movements, exacerbating dissatisfaction with the status quo and working the contradictions between ideas of reality and what it could be transformed to be…

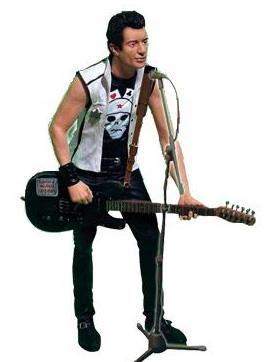

Hang on a minute wasn’t I supposed to be talking about the Strummer documentary? Well one of the interesting things about it was that the Clash weren’t really the main story. The stuff about the early Squatter, 101er days was great, it set up the DIY ethic and reminded you of the importance of that holey space where weeds can grow. Weeds of course are just plants that have escaped domestication. Then when it got to the Clash it was all a bit familiar and not quite as interesting. The real story of the film, though, was Strummer trying to recover from the harmful effects of fame. The beauty of it was that the recovery only came about when he engaged with rave, free parties and festivals – a new wave of that mix of music, politics and intense collectivity. The solution to celebrity is to dissolve into collectivity.A bit ironic then that the main fault with the film was that it was a bit star fucker. Loads of people were cut out of the story to be replaced by famous friends and admirer’s recollections. Why does any of this matter? Well one reason to talk about stuff like this is that it could help us deal with the danger of a new asceticism and purism the possibility of which can be detected in some climate change activism. The idea that ordinary people are the problem. An appreciation of how widespread the affects of revolutionary politics go may help with this. Also those affects have to be part of any calculation of what is possible. But also I think these sort of experiences are central to how we need to think about the role of the political militant. At least partly because the Strummer story is about how at certain times the creation of the common moves through a singular event. Such as the way Johnny Rotten’s style, his innovations, become the repository of people’s changing desires and then the means of their transmission. This can be a destructive experience for the people caught up in such singular events. John Lydon has obviously never recovered or dealt with its inheritance but Strummer did, or at least he made a good fist of it. Militants, and others, need to avoid getting trapped in the transcendent fictions of fame, which Strummer came to realise is illusionary. Just look at the elevation of Joss Garman from Plane Stupid as the latest activist celebrity. But it also relates to what Argentinean militants have called political sadness. Once you’ve been caught up in a singular moment – where you were an activist in your own life – how do you cope with its passing. When possibility closes up and you move from the joyful affect of powerfulness and increased collective capacities into the sadness that comes from those capacities and potential closing up. A life is made from such singular moments and “The Future is Unwritten” ends on a nice commentary from Joe when he offers us an ethic for living:

“ And so now I’d like to say: People can change anything they want to and that means everything in the world… greed is going nowhere They should have that on a billboard in Times square. Without people you’re nothing. Anyway that’s my spiel.”