Last night I gave a short talk on behalf of We Won’t Pay For Their Crisis to the Climate Chaos Cafe at The CommonPlace. There’s nothing staggeringly original in it, but it does contain some nice insights harvested from all over the place (some chunks were lifted verbatim from the latest issue of The Commoner and libcom).

WHAT DOES THE ECONOMIC CRISIS MEAN FOR THE CLIMATE CHANGE MOVEMENT?

We are in the middle of two crises, the climate crisis and the economic crisis. Although we we seem to treat them as separate, I’m going to argue that they are completely entangled. Tackling one without tackling the other is impossible or fruitless. But the connections are complex and shifting, so I want to first give a quick overview of how the economic crisis arose, before probing a little deeper…

60 YEARS IN 60 SECONDS

To understand the current economic crisis (and the collapse of what we call neo-liberalism, the most current phase of capitalism), we have to understand how it arose. And for that we have to go right back to the end of the Second World War. The post-war productivity boom was based on a ‘deal’ of higher wages in return for improved productivity – those were the days when we were told “you’ve never had it so good”. But by late 1960s this period of growth was being derailed by a wave of strikes and global unrest: in the workplace there were a growing number of struggles over time & quality of life (rather than money), while there was an explosion of anger from those excluded from this deal (i.e. anyone who wasn’t a white, skilled, male factory worker).

In the face of this, the post-war settlement was killed off in the mid- to late-1970s by a capitalist counter-attack which laid the foundations for ‘neo-liberalism’. You can pick any number of key moments – the coup in Chile in 1973, the defeat of the US air traffic controllers strike in 1981, or the defeat of the miners in 1984/5 in the UK. They were all part of a much broader systematic strategy, which played out here like this.

First, the old centres of workers’ militancy (mining, manufacturing) were dismantled and outsourced to low-wage economies overseas. In the UK in 1971 over 70% of people were employed in primary industries (like mining) or manufacturing, today over 70% of workers are in the service sector.

Second, the banking sector was massively deregulated. All sorts of complicated ‘derivatives’ markets were created. When this started to unravel in summer 2007, it ultimately resulted in the credit crunch – because no-one knew what all these pieces of paper were really worth.

Under neo-liberalism, wages were driven ever downward. I’m not alone in the fact that every pay rise I’ve had over the last 15 years has been below the rate of inflation. But while this boosts profits, the problem is that it keeps consumer spending (= economic growth) down. This problem was ‘solved’ by extending massive consumer credit, based mostly on rising house prices. This gave us the spending power to purchase all those lovely commodities coming out of the new manufacturing centres in the Far East and elsewhere. Hence the anomaly where our living standards in the UK rose at the same time as our wages as a proportion of profits kept falling.

Without primary industries or manufacturing the economy came to rely more and more on the banking and financial sector. This sector was in turn heavily reliant on rising house prices: complicated ‘mortgage derivatives’ were one of the major assets held by the big banks. So when the housing bubble burst, everything started to unravel – banks teetered on the brink of collapse, credit dried up, and the economy nosedived.

We are in uncharted waters. Despite comparisons to 1929, this level of collapse is unprecedented. How things pan out is of course partly down to us. But we don’t need a crystal ball to predict the storm that’s coming: in the UK, we’re already facing redundancies, wage cuts, benefit cuts, wage cuts, public service cuts, repossessions & evictions. Globally, there is mass social unrest on the horizon: workers laid off from thousands of factories in China have taken to the streets; food riots exploded in over 30 countries across the globe this time last year; and in the last few months we’ve seen violent battles in Latvia, Bulgaria & Iceland, not to mention Greece, Italy and France…

WHAT HAS ALL THIS GOT TO DO WITH CLIMATE CHANGE?

Obviously at a superficial level, there’s a shift of focus away from climate change, both for us as citizens/campaigners/workers/claimants and for NGOs and local and national government. Plus we now have to deal with the fact that a huge slice of public funds have been diverted into propping up financial institutions.

But we need to dig deeper. We talk about it as a “climate crisis” but from the point of view of capitalism (seen as a thing, an endlessly expanding dynamic system) it’s actually an energy crisis. And it’s an energy crisis that capital has to tackle in order to re-launch a new cycle of accumulation. This isn’t something new: the idea of “limits to growth” were an endless headache for capital in the mid-1970s before neo-liberalism took hold and unleashed new levels of exploitation.

In fact energy in its widest sense has been a permanent problem for capitalist development. Capitalism is an exploitative, ecologically destructive system but it is also incredibly dynamic. 300 years ago, when it faced down a similar twin crisis of a rebellious population and ecological crisis, its salvation was coal. Unlocking these carbon resources played a crucial role by allowing capital to substitute machinery for our labour, at a price that could sometimes be fixed years in advance and without risk of strikes, sabotage or go-slows.

It’s impossible to think about patterns of energy consumption, and therefore about global warming, without thinking of those social relations – capitalist social relations – that have shaped those patterns. The collapse of neo-liberalism and the climate crisis are intimately linked – so much so that they’re almost impossible to separate.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, for us. At the back of much of the talk around climate change has been the idea that if we can just get people to accept the thesis of “peak oil” or “global warming”, then we will be able to magically pass into a different sort of world. As if we can switch off a carbon-based economy without also switching off the material social relations that surround it. As if the relentless drive for economic growth is some sort of mad aberration that we can turn off, or tone down. It’s not. There is no accident. There are structural causes at work here: the way we reproduce ourselves socially is bound up with the way we reproduce ourselves economically and the way we reproduce ourselves ecologically. But – and this is the key thing – the global financial meltdown could lead to a recomposition of social forces that would enable the rapid switch-over we need.

To get that right, I think there are four related areas worth thinking about

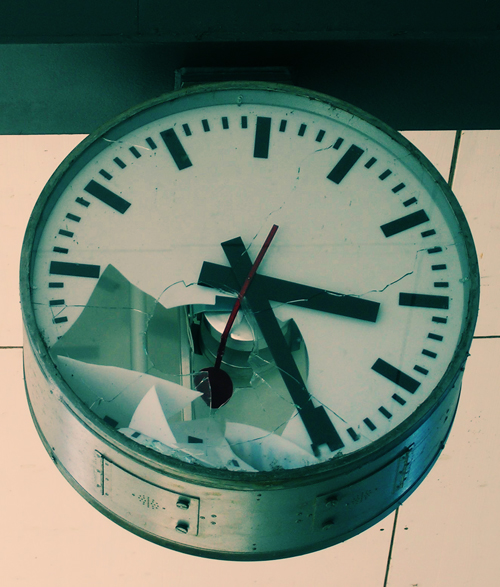

1. HOW DO WE THINK ABOUT TIME?

By this I don’t simply mean what time-scales are we thinking about, altho they are also important.

There’s a time lag in the economic crisis which mirrors the time lag in climate change

– the first cracks in sub prime sector began Aug 2007 = implosion last year

– credit crisis from last summer = redundancies & layoffs now

– £500bn bank bail-out last autumn = massive public sector squeeze for the foreseeable future

This disconnect makes our responses very problematic – by the time we act, it may be too late. But there’s an even more important aspect to this time lag. Neo-liberalism has been built on a massive expansion of debt. By mortgaging our futures (in the case of pensions quite literally) we’ve been able to put off dealing with the fact that a few are reaping massive profits on the back of our falling wages. The same deferral, the same displacement of antagonism into the future, has also been going on with climate change. Except as we know that process is non-linear: once we reach a tipping point, change will be irreversible when it comes time to pay.

This leads into a deeper connection. Capitalist social relations are based on a particular notion of time. Capital is value in process: it has to move to remain as capital (otherwise it’s just money in the bank). That moving involves a calculation of investment over time – an assessment of risk and a projection from the present into the future. The interest rate, for example, is the most obvious expression of this quantitative relation between the past, the present and the future. It sets a benchmark for the rate of exploitation, the rate at which our present doing – our living labour – must be dominated by and subordinated to our past doing – our dead labour.

It’s hard to over-state how corrosive this notion of time is. It lies at the heart of capitalist valorisation, the immense piling-up of things, but it also lies at the heart of the production of everyday life. To paraphrase George Orwell, if you want a picture of the future, imagine a cash till ringing up a sale, forever. This is true at all levels, whether for capital’s planners meeting in Davos or for us trying to make ends meet.

But this is the deeper meaning of the meltdown: just like global warming, it has brought the future crashing into the present. Interest rates are now effectively below zero. We have reached a singularity. Capital’s temporality depends upon a positive rate of interest, along with a positive rate of profit and a positive rate of exploitation – all that has collapsed. And just as with climate chaos, the debts are, quite literally, being called in.

2. HOW DO WE THINK ABOUT CHANGE?

The word ‘crisis’ has its origins in a medical term meaning turning point – the point in the course of a serious disease where a decisive change occurs, leading either to recovery or to death. So capitalism may be in crisis, neo-liberalism may be over, but that doesn’t mean we’ve won. Far from it. Crisis is inherent to capitalism. Periodic crises allow capital to displace its limits, using them as the basis for new phases of accumulation. In that respect, it’s true to say that capitalism works precisely by breaking down. But that’s only true in retrospect – after the resolution of the crisis. In fact crisis is mortally dangerous to capital, because it means an open-ness to other possibilities.

The critical instability we’re living through offers a chance for a phase transition, a rapid flip from one form of social organisation to another – or to many others. From capital’s point of view, it’s exactly this sense of openness, of possibility, that needs to be closed down. At the three major summits this year (G20 in the UK in April, G8 in Italy in July, and COP15 in Denmark in December), world leaders will be looking to contain things, to rein in our desires, and draw a line under the events of the past few months. “Move along now, there’s nothing to see here…” Every ‘solution’ that’s touted at these summits will also be an act of closure, an attempt to reintroduce capitalist temporality, one that sees the future rolling out inexorably from the present. In other words, get back to work: normal service will be resumed as soon as possible.

We have to do a fine balancing act here. On the one hand, as recession deepens, we’ll resist any measures that restrict our immediate freedoms. That might mean pushing for ‘solutions’ that are slightly less damaging, and which may therefore help capitalism off its sickbed. Individually we may accept pay cuts rather than risk redundancies (altho historically one doesn’t rule out the other). Similarly, the catastrophic build-up of greenhouse gases needs us to act quickly and decisively.

But on the other hand our greatest chance of something different lies in keeping the crisis ongoing, in keeping the future open. So we also have to resist the pressure from capital’s planners for a quick fix, whether at the G20 or at Copenhagen. As soon as crises are ‘solved’, our room for manoeuvre is diminished.

3. HOW DO WE RELATE TO THE MARKET?

As crises are closed down, the way the question is framed moves back on to a safer terrain for capital. We drift back into that temporality.

Climate change becomes a matter of carbon trading, or investment, rather than circulation of capital. It becomes a question of technical solutions and national/international policy decisions. Funnily enough, as climate change becomes the major topic at summits, it becomes fundamentally depoliticised. It’s easier to debate carbon parts per million in the atmosphere, rather than ask ourselves what sort of worlds we want to live in

It’s the same with the financial meltdown. Since last summer, it’s gone from a “banking crisis” to a “credit crunch” to an “economic crisis” to “negative economic growth” to “recession”. For months the use of the word “recession” was discouraged on the grounds that it would become self-fulfilling. But if there’s no name to what we’re living through, it can’t be normalised. And if it’s not normal, then we can behave exceptionally… So it’s officially a Recession.

We can see this move from “crisis” to “recession” in another way: a crisis for capital has become a crisis for us. Costs are shifted on to us. The massive bail-out of the banking system in the UK and the US is just the tip of the iceberg.

And it’s exactly the same with climate change. It’s obvious that costs of climate change are met disproportionately by the poor: globally it’s the poor who are most at risk of flooding, spread of disease, crop failure, resource shortages etc. And without a structural change, the costs of alleviating climate change will also be met by the poor. Three examples: green technologies are likely to remain expensive, so the poor will be shut out and forced to use “dirty” energy; agrofuel schemes which are still being forcibly rolled out across the global South (and in the US) in the face of widespread opposition; increasing enclosure of common land in the name of “conservation”, driving people away from resources that they have traditionally worked in order to sustain themselves. And in fact, as well as excluding the poor, all three have disastrous environmental consequences…

If we frame the question in this way, if we support attempts to resolve these crises through the market, and through the state, then we run the risk of engendering a green Keynesianism. In other words, a new regime of capitalist accumulation based on any combination of renewable energy, nuclear power, so-called clean coal or agro-fuels. It’s easy to see how this could make sense. You start off with the idea that in terms of life on earth “we’re all in it together”; but we need to save the economy first to enable us to have the resources to tackle the challenge…

In fact, far from being a ‘problem’ to overcome, the hope is that climate change may actually become a primary source of revenue to solve the massive fiscal problems faced by Europe and the US (but not those of the global South). Renewable energy, for example, is a huge growth sector, where demand far outstrips supply. And according to the head of UN Climate Change Secretariat: “The credit crisis can be used to make progress in a new direction, an opportunity for global green economic growth… it is an opportunity to rebuild the financial system that would underpin sustainable growth … Governments now have an opportunity to create and enforce policy which stimulates private competition to fund clean industry.”

Or as the European commission President puts it when the EU signed a new climate change deal in December “We mean business when we talk about climate”.

But if the key question isn’t whether we shift away from fossil fuels, but how, then framing the answer in terms of the market and growth is a huge and explosive contradiction.

The problem of adopting the market as a frame of reference is that capital monetizes everything, it turns everything into money. And with financialisation, that trend has become even stronger. Under neo-liberalism, one of the most important roles of the the state, locally and globally, has been to impose “good governance”. In other words, to reinforce the idea that every problem raised by struggles can be addressed – on ONE condition: that we address those problems through the market. There’s a solution for everything, as long as we buy it. Or rather as long as ‘we’ (meaning the world’s poor) pay for it. If neo-liberalism had a slogan, it would be “stop me and buy one”.

Ironically some of the pressure for this has come from green campaigners who have argued, correctly, that capitalism takes no account of environmental costs when calculating price. But under the dictatorship of the market, money has become the measure of all things. The market tries to make commensurable things that are incommensurable. But how can you ‘sell’ the right to emit carbon? Or to poison water supplies?

This isn’t simply an ethical question, one of value against values. The idea of price is also based on linear dynamics. What price can you put on something when you can no longer calculate the probable outcome? As sea levels rise, it’s easy to predict coastal flooding. But then there’s the amount and pattern of rainfall, a probable expansion of the subtropical desert regions, Arctic shrinkage and resulting Arctic methane release, increases in the intensity of extreme weather events, changes in agricultural yields, modifications of trade routes, glacier retreat, species extinctions and changes in the ranges of disease vectors… Put that in your calculator.

4. HOW DO WE RELATE TO THE STATE?

With neo-liberalism in crisis, and the threat of irreversible climate change, the state’s role is going to become increasingly crucial. A de-carbonised global capitalism is not impossible. But it will require even higher levels of “discipline”. Austerity will have to be enforced on a massive scale.

As I said earler, capitalism is value in process – like a shark, it needs to keep moving or die. But this drive to self-expansion means it needs an ever-increasing energy base. Let’s look at it from the perspective of capitalism. The logic of capitalist growth is that it will always seek to externalise its costs. If we imagine there’s a three-way relation between capital, us and the environment (although none of these three things are actually discrete), then limits enforced in one sphere re-surface as intensified exploitation in another. If capital can’t rob one, it will rob the other. Leaving the coal in the hole, on its own, means more energy sucked from our bodies…

Let’s not forget that the last capitalist era of renewable energy (the age of sails and windmills) was also a time of slavery, genocide and enclosures on a massive scale

CONCLUSION

There are no easy answers here. The ground on which we’re fighting is shifting far too fast for that. But one thing to bear in mind is that movements rarely take straightforward forms.

In 1905 the Russian revolution which threw up the first Soviets began with a small strike by typesetters at a Moscow print-works: they wanted a shorter working day, a higher rate of pay, and the right to be paid for apostrophes. In France the uprising of May 68 was sparked in part by a student protest which began in Nanterre with a fight over demand for boys to be let into girls’ dormitories…

Last week a wave of wildcat strikes swept through UK oil refineries. They were hugely controversial, unpredictable, and came out of nowhere. Who knows their long-term meaning? And is it a coincidence that they happened in the energy sector?

What I’m trying to say is that real powerful interventions around climate change may well come from people and areas who don’t explicitly identify with climate change politics. They may take the shape instead of food riots, struggles against property developers, fuel poverty campaigns etc

There are two key points of intervention coming up. On 2 April the G20 are meeting in London’s Docklands. There’ll be a Climate Camp in the Square Mile in the City of London on 1 April. Then in December Copenhagen sees the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP15). There’s a huge mobilisation underway amid an ongoing debate about what attitude we should adopt. Inside? Outside? One foot in? It’s been given added significance because will be almost exactly 10 years since the WTO shutdown in Seattle.

Before that, We Won’t Pay for Their Crisis are having a meeting on Saturday 28 February. It’s called ‘We are an image from the future’ and we will be picking up some of these themes and trying to relate them to recent events across Europe.

Oh dear, last weeks wide-eyed talk of green shoots have already been replaced by a new sense of gloom and talk of a double dip recession. That must rank amongst the shortest, least noticeable economic recoveries in history. I suppose wishful thinking can only get you so far. Ultimately the pundits and spinners are going to have to face up to the idea that the present economic crisis is not just a normal moment in the usual cycle of boom and bust but is a more fundamental and potentially epochal affair.

Oh dear, last weeks wide-eyed talk of green shoots have already been replaced by a new sense of gloom and talk of a double dip recession. That must rank amongst the shortest, least noticeable economic recoveries in history. I suppose wishful thinking can only get you so far. Ultimately the pundits and spinners are going to have to face up to the idea that the present economic crisis is not just a normal moment in the usual cycle of boom and bust but is a more fundamental and potentially epochal affair.